memo

In modern Japan, altering the face value of banknotes by changing or cutting them is punishable by law.there isHowever, in 1945, at the end of World War II, Finland took measures to physically devalue its currency, ordering citizens to cut their high-value banknotes in half.

Moneyness: Setelinleikkaus: When Finns snipped their cash in half to curb inflation

https://jpkoning.blogspot.com/2024/11/setelinleikkaus-when-finns-snipped.html

Leikattu seteli on harvinaisuus – Taloustaito.fi

https://www.taloustaito.fi/vapaalla/leikattu-seteli-on-harvinaisuus/

Dramaattinen pakkolaina – sakset käteen ja seteli kahtia – Suomen MonetaSuomen Moneta – keräilijän kumppani, rahojen ja mitaleiden asiantuntija

https://www.suomenmoneta.fi/blogi/221-dramaattinen-pakkolaina-sakset-kaeteen-ja-seteli-kahtia

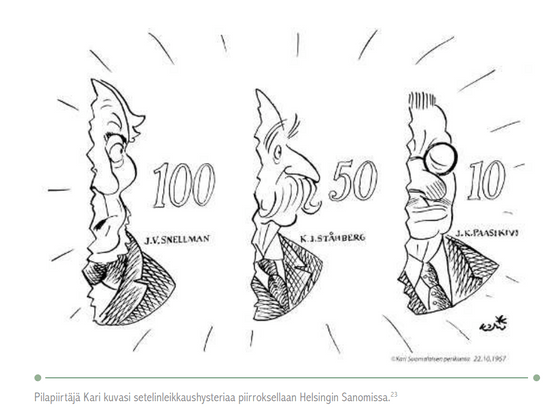

According to John Paul Corning, an expert on transit economics, the Finnish government instructed citizens to cut their banknotes in half on New Year’s Eve in 1945.Setelinleikkaus (banknote cutting)It is said that this was carried out.

As a result, Finnish citizens received 5000 denomination banknotes early in the new year of 1946.Markka1000 and 500 marka banknotes were to be cut with scissors.

The cut notes could still be used to buy goods, but their value was half their face value. In other words, the left half of a 1,000 marka note could only buy items up to 500 markkas. The right half of the remaining banknotes was treated as a forced loan to the Finnish government, and became a bond that could not be used for purchases.

This is not an unprecedented measure, and is said to be a policy modeled on similar measures taken in Greece in 1922 and Norway and Denmark in 1945.

In 1990, economists Rudiger Dornbusch and Holger C. Wolf explained why people went out of their way to cut banknotes.paperexplains that it was a response to the currency surplus problem in postwar Europe.

At the time, European citizens had accumulated a considerable amount of “involuntary postponement of consumption” due to years of wartime production systems, price controls, and rationing, or in other words, forced savings that they had no choice but to set aside because they could not use it even if they wanted to.

With the end of World War II, they thought of returning to their previous lives, but as many factories had been destroyed during the war and production had declined, a serious shortage of supplies was expected. Ta.

There were concerns that a shortage of goods would cause a sudden rise in the prices of goods, or inflation.

The same thing is happening with the coronavirus pandemic. The global economy has been suffering from rapid inflation due to the lockdowns and supply chain disruptions from 2020 to 2021, which were compounded by increased spending and unused aid funds due to the end of lockdowns. Masu. In addition, starting in 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused energy and food prices to soar, and in a sense this can be said to be inflation brought about by the war.

Returning to Finland just after World War II, the Finnish government at the time cut its banknotes in half in response to the impending hyperinflation crisis in order to halve the purchasing power of the people and curb consumption. The public was asked to use the left half of the banknotes to make purchases or take them to the nearest bank to exchange them for new banknotes.

The right half of banknotes that could no longer be used were required to be registered with the government, and once registered, they were to be redeemed in 1949 as Finnish national bonds with an annual interest rate of 2%. As a result, the Finnish government tried to postpone half of the people’s consumer confidence to four years later. There were also suspicions that Germany was taking large amounts of funds away from Finland and creating counterfeit banknotes, and there was also speculation that Germany wanted to switch to new banknotes as soon as possible.

In conclusion, this policy did not work well and the Finnish economy suffered from inflation for some time afterwards. This is because the policy did not apply to deposits, and since cash covered only 8% of the total money supply at the time, a large portion of the currency surplus remained untouched.

It is also said that one of the reasons for the failure was that many Finns knew in advance that drastic inflation measures were to be taken and protected their assets by converting cash into savings or real estate.

In the end, the poor and those living in rural areas were especially borne the brunt of the economic turmoil.

The bold policy of cutting the money in wallets in half and its failure was etched in the minds of Finns as a strong sense of distrust, and even when the devaluation of the Markka was discussed in 1967, there were concerns about cutting the banknotes again. There seems to be some suspicious information circulating.

Copy the title and URL of this article